“Come and join us!” the vampire beckons. “Won’t cost much to be young and beautiful. Just your soul.”

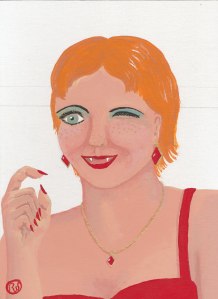

Carletta, the femme fatale of the first two AVS novels-in-progress, epitomizes a standard of youth and beauty. Few can see her fangs. Few know the snares she hides. Are the benefits she offers worth the heartache, and more?

When people learn I’m writing vampire fiction, many say, “Good for you, that’s a very popular subject right now.” And they’re right. Vampire books abound, you can take your pick of vampire shows and movies, rock artists sing about them, and the web abounds with them. Some agents and editors even discourage writers from the subject because the market is flooded. They want something new—no more vampires, or at least a really fresh angle on them. I trudge on with my project, not so much because of the craze but because I have something to say that I believe is fresh as well as important.

Why are people so interested in vampires today, anyway?

The reasons are myriad. One is that the vampire holds time still, freezing youth in its place. The fountain of youth has such an appeal that some people, fictional or real, will pay any price for it—even blood. Even their souls.

It’s not a new phenomenon. High up in the “real vampire” hall of fame, Elizabeth Bathory bathed in the blood of her virgin maids, convinced that the blood of these poor slaughtered young women gave her youthful beauty.

Barbarism from a previous century, to be sure. But is the present any kinder or more enlightened? What about our own society’s views on beauty? When women who all but give up eating to be walking skeletons are unknowns, we call them anorexics—victims of a disease. But if they are famous—supermodels. Is this not vampirism turned inward? And who drives these poor women to think this way about themselves?

The destruction of the self is an evil close to the destruction of others. I think we need to ask where the anorexia epidemic comes from. Our society’s worship of thin, youthful beauty and its impossible image of “perfection” pay a key role. Who is preying on whom?

Unlike today’s glamorous images, the vampire of ancient folklore was ugly and strange-looking, befitting of a demonically animated corpse. Even Stoker’s Dracula had pointed ears and extra hair, including on the palms of his hands. But today’s vampire fiction abounds with the promise that people who turn into vampires will have perfect, youthful beauty. In Anne Rice’s The Vampire Lestat, said vampire finds a huge collection of slim, blond young men that his maker, Magnus, discarded and locked up to die in attempt to make the perfect pretty boy (page 93-94, Alfred A. Knopf, NY, 2004). It’s completely a matter of looks. In Christopher Moore’s You Suck, a Love Story, the newly-turned Tommy is returned to a state of infancy in that his acne disappears and his toes straighten as if he has never worn shoes. Jody, who changed him, exclaims, “You’re perfect!” (emphasis mine). Jody says her split ends went away but she’s uncomfortable that she’s stuck needing to lose five pounds (page 7, William Morrow–NY, 2007). In the Twilight saga, Stephenie Meyer continually describes its perpetually teenage vampire hero’s features as perfect and even angelic. All the vampires are so angel-like in appearance, in fact, that they sparkle like diamonds in sunlight. To obtain this beauty for herself, the heroine gladly risks her soul.

The vampire’s lure is bigger than fiction and bigger than actual killers like Bathory. It lurks in the eyes of the supermodel’s audience and our own eyes as we look in the mirror. Do we fear aging and death so much that we would be willing to destroy our own lives and others’ to preserve our own? Is looking beautiful worth more than life itself to us? If so, perhaps vampires are real.